In May of 1966, the magazine Lucha Libre got a refresh. The magazine was always a little bit grounded in reality, but they pushed more that way. The prose fiction stories which had been a staple since the first issue was replaced in issue 135 with true crime stories, there were more photos added instead of illustrations and always a few pages of color portraits for autographs. They also swapped out the illustrations of scantily clad women with photos of scantily clad women. Lucha Libre was in a publishing war with rival Box y Lucha magazine. I don’t have access to those issues of this period but feels in response to either whatever they were doing, or how they were selling.

The “realness” didn’t end with just the photographs. Starting in issue 136 (cover date May 29, 1966), magazine director Valente Perez started a series entitled “La Verdad de La Lucha”. It is listed with Perez’s name as the byline, while every other article in the magazine continues to be listed under pseudonyms and nicknames. Perhaps Perez wanted to guarantee any trouble from the articles was going to go directly to him, because there obviously would be trouble. Perez explains in one of the biggest publications in lucha libre that all matches finishes are predetermined, that it is all a show, and that’s a good thing.

While people knew wrestling matches could and often be fixed maybe as early as the 1800s, it is still nothing you see normally mentioned in a publication covering the shows. It is definitely never spelled out or explained as Valente Perez does in this series at that time, and rarely even now in general. Just recently, UFC’s Cain Velazquez plainly saying lucha libre was totally fake stirred up a minor firestorm (and sure didn’t endear him to the Mexican public like the interview was probably designed.) La Parka dedicated his column in Record the following week to saying Velazquez didn’t know what he was talking about and must have confused what he saw at the WWE Performance Center with the real lucha libre La Parka practices – and then the press asked about it again at the TripleMania press conference. Any wrestling fan who cares enough can find out not just that wrestling is a show but how they put the show together today by a quick google search, and yet the wrestling promotions still insist on maintaining the illusion of what they’re doing as a legitimate sport. If Velazquez was a journalist covering wrestling, or if Perez wrote these same articles today, they’d probably be restricted from attended shows. It is crazy to think someone would do the same fifty years ago, suggesting Perez might have just had enough power in a more compact media landscape to get away with it.

I’m posting these pages here, so perhaps people with better Spanish reading skills may get something more out of them. I’m not putting watermarks on them, so I suspect they’ll be on Facebook soon enough. These issues appear to be photographed from a collection in from the Mexican national archive. The set of issues has been passed around for a while, but I’ve never seen anyone post these pages. You can get full size versions of the photos below by clicking on them.

The series starts with quotes from unnamed people who hold important jobs, identifying themselves as lucha libre fans who know it is a show but enjoy it all the same. The point is the wrestling fanbase is not made up of dumb people being followed, but smart people who maybe don’t understand how everything works but do understand it is not a traditional sport. The article sets on explaining some of those ways lucha libre works. The blows are not what they seem and couldn’t be – if they were truly hurting each other as much as being portrayed, everyone would be in the hospital instead of wrestling three times a week. There are matchmakers who decide who wins or losses, depending on what decision will make the promotion more money and not necessarily who is the more skilled wrestler. Though sometimes those decisions are made based on what happens in practice; a wrestler who doesn’t train hard enough may not get wins. The rest of the match are up to the wrestlers and not scripted.

Perez classifies luchadors into three types: Los Maestros, Los Inofensivos, and Los Fajadores. Los Maestros are the most skilled, said to be versed in the techniques to win matches if it was all actually real. Los Inofensives are a middle ground, luchadors who can pass for credible matches fine but don’t really have the skill to hurt someone. Los Fajadores can’t even fake it well. The greatest maestros off at the time, in Perez’s view, are Raul Romero, Diablo Velasco, and Rolando Vera.

In Issue 137, there’s a continued explanation of what is and isn’t real. Valente Perez seems to imply that first falls of matches are ‘real’, or at least sometimes competitive, as the wrestler themselves attempt to find out which of them is the better grappler. The rest of the match is for the fans, who Perez believes are not knowledgable enough to appreciate the skill or hard work in a ‘real’ match lacking spectacle. Those early exchanges still are important to Perez – it’s a proof of a wrestlers abilities, and he derides the increase of “Los Payasos del Ring” who don’t treat it seriously.

Valente Perez addresses blood in wrestling. This is before the fan idea of blood packets. Apparently, the fan theory of the day was an oily substance called “anilina” was being used to simulate blood. Perez offers 10,000 pesos to anyone who can submit proof of this ever happening He insists that any time blood has been seen, it has been real blood. There’s nothing here I picked up that specifically suggests blading, and I’m not sure if that was the process at the time. There is talk about wrestlers knowing the easiest ways to open old wounds to get that blood.

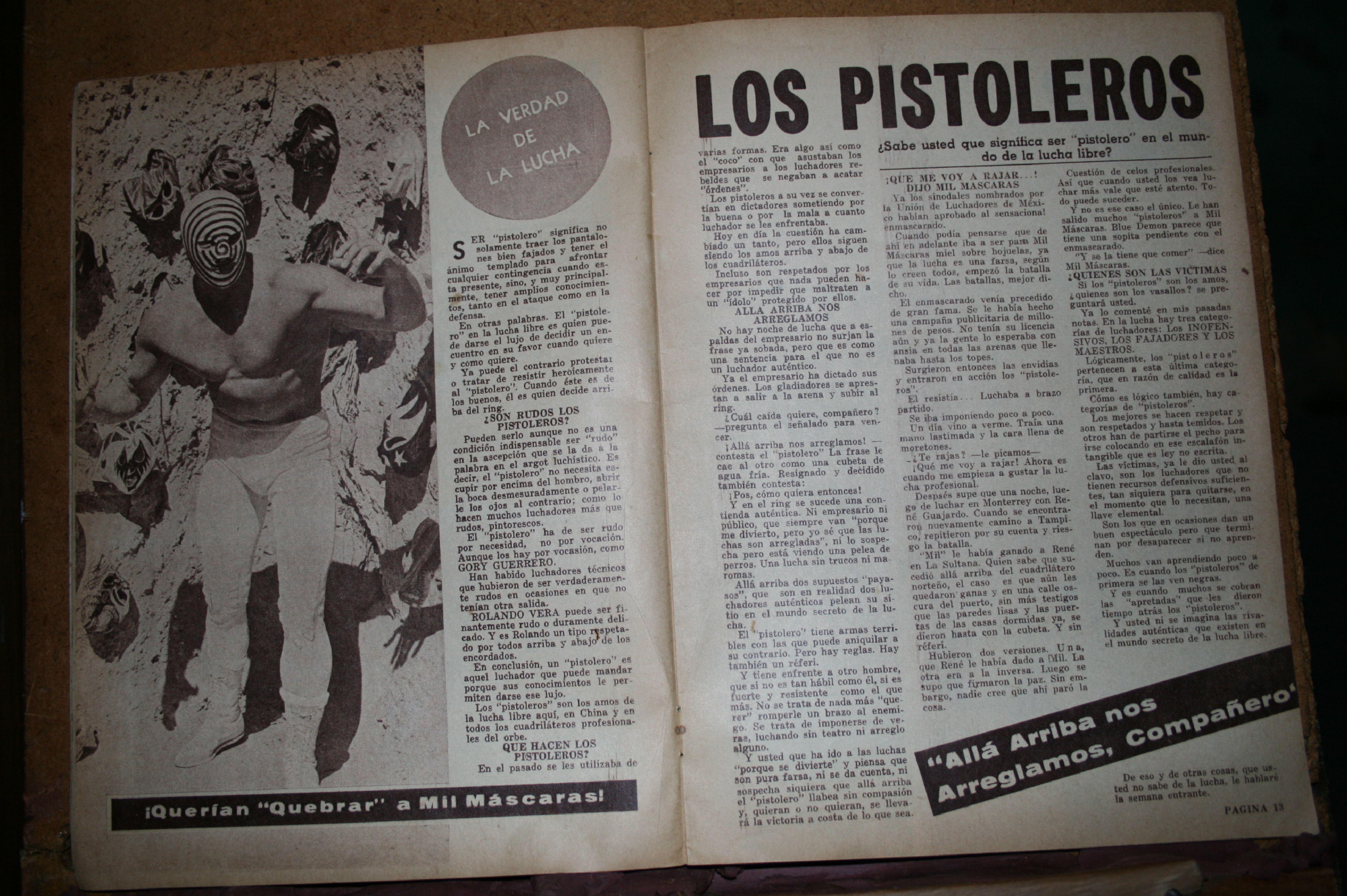

There’s also a section on insider terms. “Arriba” & “Abajo” are used instead of win or loss. “Registrar” is kind of selling, which people still use the idea of registering blows. Young Mil Mascaras is referred to as “pistolero”, a strong guy who can do whatever he wants in the ring. The article ends with a tease of more Pistoleros next week.

The sections are a little shorter starting in Issue 138. The article this week is talk just about famous Pistoleros of wrestling. Valente Perez explains Pistoleros as almost shooter types here, explaining they can do whatever they want in the ring without anyone stopping them, and are dedicated to keeping the standards of lucha libre high. Gory Guerrero and Rolando Vera are mentioned as two of the best.

Tarzan Lopez is said to the best Pistolero & maestro of the 40s/50s in Issue 139. He had “the body of a dog” but was actually very strong and a big star. The fans loved him, the wrestlers not so much for the way he treated them. He would not always listen to the promoters orders, especially if it was a wrestler he did not respect – he was known to have humiliated wrestlers he was meant to be put over in the ring. There is a story of a younger, more powerful El Gladiador deciding to have a go at Lopez in the ring and being sent back to the gym humiliated. Lopez and Gory Guerrero hated each other, which led to Guerrero telling his fellow wrestlers – not the fans – that he was going to go after Lopez in a match in Veracruz.

Valente Perez does not get back to that story in Issue 140, instead of speaking about El Santo. This is not the issue where the cover calls El Santo a paper idol – it is in the following issue, for whatever reason – but it definitely meant to be the story attached to that headline. Perez says Santo was just a midcard wrestler in Arena Coliseo when Medico Asesino was the top guy on Televcentro’s TV wrestling program in the early 50s, and Santo only ascended to the top because of publicity. Perez gives Santo credit for being a top ticket seller (taquillero), but labels him an “Inofensivos” and not a top level wrestler. Rolando Vera is said to have refused to lose a title match to El Santo at one point. He told EMLL to have Santo try and take it from him in the ring and they didn’t bother, knowing Vera would win in a real fight. It is not said when this happened, though there’s a sketchy period with the NWA Middleweight Championship and those two men in 1956 which could be connected.

Santo is not expected to wrestle too much longer as it is. Between injuries, his movie obligations, and the amount of money he’s already made, Perez doesn’t think he’ll last much longer in wrestling. Perez would be happy if he wants away, sort of revealing the true purpose of this particular article. Santo made some unflattering comments about Mil Mascaras in “the blue magazine” (Box Y Lucha.) Lucha Libre magazine is behind Mil Mascaras 100% and saw it as Santo being jealous that young Mil is obviously going to take his spot as the top star in Mexico and trying to sabotage it before it can happen. Santo questioned Mil’s abilities, which Perez finds ridiculous since Mil is a true pistolero and Santo isn’t on his level. Perez tells Santo to smarten up or go home to his money.

The series concludes in Issue 141, which is a long retelling of that Tarzan Lopez/Gory Guerrero match. That match wouldn’t have been filmed and it would’ve been unlikely that Perez traveled to see it, so I suspect he’s going on word from other wrestlers who were smartened up to what happened. The short version of the long story is Gory Guerrero caught Tarzan Lopez in a hold he could not escape before Lopez even totally realized what was going on, and Lopez had no choice but to give up. It is said the fans had no idea what was going on – that is, they didn’t think anything special had gone on, not that the action looked confusing. Lopez definitely knew what happened and there was a confrontation in the locker room later. Guerrero didn’t back down, Lopez gave him some respect, and the article implies he left wrestling soon after. In this telling, Tarzan Lopez comes off like the bully who finally got beat by a bigger man and slumped off into the sunset.

Valente Perez ends that article by mentioning the series is going on hold while he leaves to cover the World Cup. The cover continues to be one week ahead of the article subjects for this last issue. It appears the next article was meant to be the real names of various wrestlers. I jumped ahead to the articles to see if that, or any other La Verdad articles turned up. There didn’t seem to be any in the next dozen issues. (I’ll bring it back here if it turns up later in the run I have.) There also doesn’t appear to be any consequences for revealing these secrets. The rest of the sections of the magazine continue on like normal, with an occasion fan letter thanking the magazine for the series and no apparent restriction of access. It seems like a big deal but there’s no sign of a reaction.

Excellent post, Cubs! Thanks for sharing this info. Much appreciated.

Thanks for this post. Interesting and we’ll done.

valente perez sounds like a real grapplefuck dude.

he does implies blading, but says that only untalented luchadores recur to it, and true masters always bleed the hard way.

the whole series is full of this weird implication that yes, matches are fixed, but that wrestling is more real than people that think are in the know suspect.

like his telling of the tarzan lopez vs gory guerrero match: he’s telling “the truth”, but definitely it’s a story mythifying both men.

also very interesting: the use of the term ‘registrar’ as a synonym of ‘selling’. i had never heard the spanish term for selling, but don’t know if they still use it.

thanks a lot cubs, this is really interesting.